Sometime later, a monk from a local monastery passed nearby the same hill. Hearing a great and raucous clamor the imam investigated. "I am over tired and have fallen asleep at prayer again, for surely I must be dreaming!" thought the imam, for before him danced a local goat-herder and his goats. The imam rubbed his eyes, but the merry dancers remained. He pinched himself, yet still the boy and his goats spun, jumped, and whirled. Aghast, the imam pulled Kaldi away and demanded an explanation for such bizarre behavior. After many questions the imam deduced that this energetic glee must have at its root the red fruit growing about them. Seeking greater understanding, he gathered some for further testing at his monastery. It was there he at last sampled the cherry himself and became infused with a great joie de vivre. That night, the imam spent more hours at prayer than ever before. "This is no ordinary fruit!" exclaimed the imam. Realizing the spiritual value of such a gift, he shared it so that all his fellow monks would remain energetic and pray with greater fervor.

And so the legend goes. Today, coffee has become the second most valuable commodity in the world after oil and 125 million people today depend on coffee for their livelihood. The World Bank estimates that nearly 500 million people are involved in the business, if you include all of the ancillary industries that provide their wares to the coffee consumer. Coffee has become big business, and with the recent explosion in coffeehouses around the world, it shows no sign of slowing down.

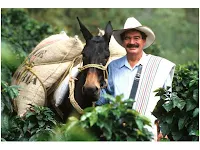

I will admit, this topic for me was a complete no brainer. As I sit writing this, a hot, steaming cup sits on the desk invigorating me with its aroma. I will also admit that I probably overdo my consumption of the ancient elixir. I drink it all day, in fact, I am rarely without a full cup when working here in the office. One thing, dear reader, I can guarantee. My java predilection will result in an informative, fun and quite thorough look into the world of coffee. I must pause here....I could swear that I just saw a mustachioed gentleman in a sombrero and leading a donkey just pass by the office window. Hmmm...oh well, I digress. Must have been my imagination. Let us begin...

History

The history of coffee has been recorded as far back as the ninth century. At first, coffee remained largely confined to Ethiopia, where its native beans were first cultivated by Ethiopian highlanders. However, the Arab world began expanding its trade horizons, and the beans moved into northern Africa and were mass-cultivated. From there, the beans entered the Indian and European markets, and the popularity of the beverage spread.

The word "coffee" entered the English lexicon in 1598 via Italian caffè. This word was created via Turkish kahve, which in turn came into being via Arabic qahwa, a truncation of qahhwat al-bun or wine of the bean. Islam prohibits the use of alcohol as a beverage and coffee provided a suitable alternative to wine. The earliest mention of coffee may be a reference to Bunchum in the works of the 10th century CE Persian physician Razi, but more definite information on the preparation of a beverage from roasted coffee berries dates from several centuries later.

The word "coffee" entered the English lexicon in 1598 via Italian caffè. This word was created via Turkish kahve, which in turn came into being via Arabic qahwa, a truncation of qahhwat al-bun or wine of the bean. Islam prohibits the use of alcohol as a beverage and coffee provided a suitable alternative to wine. The earliest mention of coffee may be a reference to Bunchum in the works of the 10th century CE Persian physician Razi, but more definite information on the preparation of a beverage from roasted coffee berries dates from several centuries later.The most important of the early writers on coffee was Abd al-Qadir al-Jaziri, who in 1587 compiled a work tracing the history and legal controversies of coffee entitled Umdat al safwa fi hill al-qahwa. (glad I had to type that and not say it) He reported that one Sheikh, Jamal-al-Din al-Dhabhani, mufti of Aden, was the first to adopt the use of coffee (circa 1454). Coffee's usefulness in driving away sleep made it popular among Sufis. A translation traces the spread of coffee from Arabia Felix (the present day Yemen), northward to Mecca and Medina and then to the larger cities of Cairo, Damascus, Baghdad and Istanbul.

|

| Mehmet Ebussuud el-İmadi |

Similarly, coffee was banned by the Ethiopian Orthodox Church some time before the 17th century. However, in the second half of the 19th century, Ethiopian attitudes softened towards coffee drinking, and its consumption spread rapidly between 1880 and 1886; according to Richard Pankhurst, "this was largely due to Emperor Menelek , who himself drank it and to Abuna Matewos, who did much to dispel the belief of the clergy that it was a Muslim drink."

How coffee came to Europe

|

| Cafe Florian, Venice |

Coffee was first imported to Italy. At that time, trade between the Italian city of Venice and the Muslims in North Africa, Egypt and the East brought a large variety of African goods, including coffee, to this leading European port. Venetian merchants, always looking toward higher profits, decided to introduce coffee to the wealthy in Venice, charging them heavily for the beverage. It really became a sought after beverage when it was "baptized" by Pope Clement VIII in 1600, despite appeals to ban the 'Muslim' drink. The first European coffee house (apart from those in the Ottoman Empire, mentioned above) was opened in Italy in 1645.

England

The drink then found its way to England largely through the efforts of the British East India Company and the Dutch East India Company. The first coffee-house in England was opened in St. Michael's Alley in Cornhill. The proprietor, Pasqua Rosée was the servant of Daniel Edwards, a trader in Turkish goods. Edwards imported the coffee and assisted Rosée in setting up the establishment. The popularity of coffeehouses spread rapidly and by 1675, there were more than 3,000 coffeehouses in England.

France

.jpg) |

| Thevenot |

Austria

The first coffee-house in Austria opened in Vienna in 1683 after the Battle of Vienna, by using supplies from the spoils obtained after defeating the Turks. The officer who received the coffee beans, Polish military officer of Ukrainian origin, Jerzy Franciszek Kulczycki, opened the coffee house and helped popularize the custom of adding sugar and milk. Until recently, this was celebrated in Viennese coffee-houses by hanging a picture of Kulczycki in the window. Melange is the typical Viennese coffee, which comes mixed with hot foamed milk and a glass of water.

The first coffee-house in Austria opened in Vienna in 1683 after the Battle of Vienna, by using supplies from the spoils obtained after defeating the Turks. The officer who received the coffee beans, Polish military officer of Ukrainian origin, Jerzy Franciszek Kulczycki, opened the coffee house and helped popularize the custom of adding sugar and milk. Until recently, this was celebrated in Viennese coffee-houses by hanging a picture of Kulczycki in the window. Melange is the typical Viennese coffee, which comes mixed with hot foamed milk and a glass of water.Holland

The race among Europeans to make off with some live coffee trees or beans was eventually won by the Dutch in the late 17th century, when they allied with the natives of Kerala against the Portuguese and brought some live plants back from Malabar to Holland, where they were grown in greenhouses. The Dutch began growing coffee at their forts in Malabar, India, and in 1699 took some to Batavia in Java, in what is now Indonesia. Within a few years the Dutch colonies (Java in Asia, Surinam in Americas) had become the main suppliers of coffee to Europe. Today, coffeehouses in Holland are synonymous with not only coffee berries, but cannabis "buds" as well. *-)

The race among Europeans to make off with some live coffee trees or beans was eventually won by the Dutch in the late 17th century, when they allied with the natives of Kerala against the Portuguese and brought some live plants back from Malabar to Holland, where they were grown in greenhouses. The Dutch began growing coffee at their forts in Malabar, India, and in 1699 took some to Batavia in Java, in what is now Indonesia. Within a few years the Dutch colonies (Java in Asia, Surinam in Americas) had become the main suppliers of coffee to Europe. Today, coffeehouses in Holland are synonymous with not only coffee berries, but cannabis "buds" as well. *-)The Caribbean and the Americas

Chevalier Gabriel Mathiew de Clieu brought sprouts from the Noble Tree to Martinique in the Caribbean circa 1714. Those sprouts flourished and 50 years later there were 18,680 coffee trees in Martinique enabling the spread of coffee cultivation to Haiti, Mexico and other islands of the Caribbean. The Noble Tree also found its way to the island of Réunion in the Indian Ocean known as the Isle of Bourbon. The plant produced smaller beans and was deemed a different variety of Arabica known as var. Bourbon. The infamous Santos coffee of Brazil and the Oaxaca coffee of Mexico are the progeny of that Bourbon tree.

In 1727, the Emperor of Brazil sent Francisco de Mello Palheta to French Guinea to obtain coffee seeds to become a part of the coffee market. Francisco initially had difficulty obtaining these seeds yet he captivated the French Governor's wife and she in turn, sent him enough seeds and shoots which would commence the coffee industry of Brazil. In 1893, the coffee from Brazil was introduced into Kenya and Tanzania (Tanganyika), not far from its place of origin in Ethiopia, 600 years prior, ending its transcontinental journey.

Production

For many decades in the 19th and early 20th centuries, Brazil was the biggest producer of coffee and a virtual monopolist in the trade. However, a policy of maintaining high prices soon opened opportunities to other nations, such as Colombia, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Indonesia and Vietnam, now second only to Brazil as the major coffee producer in the world. Large-scale production in Vietnam began following normalization of trade relations with the US in 1995. Nearly all of the coffee grown there is Robusta. Despite the origins of coffee cultivation in Ethiopia, that country produced only a small amount for export until the Twentieth Century, and much of that not from the south of the country but from the environs of Harar in the northeast.

The Kingdom of Kaffa, home of the plant, was estimated to produce between 50,000 and 60,000 kilograms of coffee beans in the 1880s. Commercial production effectively began in 1907 with the founding of the inland port of Gambela, and greatly increased afterwards: 100,000 kilograms of coffee was exported from Gambela in 1908, while in 1927-8 over 4 million kilograms passed through that port. Coffee plantations were also developed in Arsi Province at the same time, and were eventually exported by means of the Addis Ababa - Djibouti Railway. While only 245,000 kilograms were freighted by the Railway, this amount jumped to 2,240,000 kilograms by 1922, surpassed exports of "Harari" coffee by 1925, and reached 9,260,000 kilograms in 1936.

The Kingdom of Kaffa, home of the plant, was estimated to produce between 50,000 and 60,000 kilograms of coffee beans in the 1880s. Commercial production effectively began in 1907 with the founding of the inland port of Gambela, and greatly increased afterwards: 100,000 kilograms of coffee was exported from Gambela in 1908, while in 1927-8 over 4 million kilograms passed through that port. Coffee plantations were also developed in Arsi Province at the same time, and were eventually exported by means of the Addis Ababa - Djibouti Railway. While only 245,000 kilograms were freighted by the Railway, this amount jumped to 2,240,000 kilograms by 1922, surpassed exports of "Harari" coffee by 1925, and reached 9,260,000 kilograms in 1936.Australia is a minor coffee producer, with little product for export, but its coffee history goes back to 1880 when the first of 500 acres began to be developed in an area between northern New South Wales and Cooktown. Today there are several producers of Arabica coffee in Australia that use a mechanical harvesting system invented in 1981.

Biology

Coffea (coffee) is a large genus (containing more than 90 species) of flowering plants in the family Rubiaceae. They are shrubs or small trees, native to subtropical Africa and southern Asia. After their outer hull is removed, the seeds are commonly called "beans." Coffee beans are widely cultivated in tropical and sub-tropical countries on plantations, for both local consumption and export to every other country in the world. Coffee ranks as one of the world's most valuable and widely traded commodity crops and is an important export of a number of countries.

When grown in the tropics, coffee is a vigorous bush or small tree which usually grows to a height of 3–3.5 m (10–12 feet). Most commonly cultivated coffee species grow best at high elevations. Although they are hardy and capable of withstanding severe pruning, they are nevertheless not very tolerant of sub-freezing temperatures and hence cannot be grown in temperate climate zones. To produce a maximum yield of coffee berries the plants need substantial amounts of water and fertilizer. Since they grow best in alkaline soils, calcium carbonate and other lime minerals are sometimes used to reduce acidity in the soil, which can occur due to run off of minerals from the soil in mountainous areas. The caffeine in coffee "beans" is a natural defense: a toxic substance which repels many creatures that would otherwise eat the seeds - as with the nicotine in tobacco leaves.

Arabian Coffee

This is the quintessential coffee of the world. Arabia lends its name to the highest quality coffee plant in the world, Coffea Arabica. This coffee accounts for about 80% of all coffee produced in the world. It prefers higher elevations and drier climates than its cousin C. Robusta.

The tropics of South America provide ideal conditions for growing Arabian Coffee, which grows best between 3,000 and 6,500 feet but has been grown as high as 9,000 feet. Generally, the higher the plant is grown the slower it matures. This gives it time to develop the internal elements and oils that give coffee its aromatic flavor. It is said that all the Arabica Coffee grown in the world started from this plant as cuttings were transplanted all over the world. Coffee from Arabia is truly the source of all coffee throughout the world.

There are several species of coffee that may be grown for the beans, but Coffea arabica is considered by many, to have the best overall flavor and quality. The other species (especially Coffea canephora (var. robusta)) are usually grown on land unsuitable for Coffea arabica. The tree produces red or purple fruits (drupes), which contain two seeds (the "coffee beans", which — despite their name — are not true beans, which are the seeds of the legume family). In about 5-10% of any crop of coffee cherries, the cherry will contain only a single bean, rather than the two usually found. This is called a 'peaberry', which is smaller and rounder than a normal coffee bean. It is often removed from the yield and either sold separately, (as in New Guinea Peaberry) or discarded.

The tree of Coffea arabica will grow fruits after 3 – 5 years and will produce for about 50 – 60 years (although up to 100 years is possible). The blossom of the coffee tree is similar to jasmine in color and smell and the fruit takes about nine months to ripen. Worldwide, an estimated 15 billion coffee trees are grown on 39,000 sq miles of land. Shade grown coffee

In its natural environment, coffea most often grows in the shade. However, most cultivated coffee is produced on full-sun, mono-cropping plantations, as are most commercial crops, in order to maximize production per unit of land. This practice is, however, detrimental to the natural environment since the natural habitats which existed prior to the establishment of the plantations are destroyed, and all non-Coffea flora and fauna are suppressed - often with chemical pesticides and herbicides. Shade-grown coffee is favored by conservationists, since it permits a much more natural, complex ecosystem to survive on the land occupied by the plantation. Also, it naturally mulches the soil it grows in, lives twice as long as sun-grown varieties, and depletes less of the soil's resources - hence less fertilizer is needed. In addition, shade-grown coffee is considered by some to be of higher quality than sun-grown varieties, as the cherries produced by the Coffea plants in the shade are not as large as commercial varieties; some believe that this smaller cherry concentrates the flavors of the cherry into the seed (bean) itself. Shade-grown coffee is also associated with environmentally friendly ecosystems that provide a wider variety and number of migratory birds than those of sun-grown coffea farms.

Health properties of Green Coffee

Green coffee beans are a rich source of antioxidants, such as polyphenols and mannitol producing good protection against chemical oxidation. The high content of arabinogalactans can stimulate the immune system of the gastrointestinal tract and might help to overcome problems of irritable colon or inflammable bowel diseases. Extracts of green coffee have been shown to improve vasoactivity (the ability of the blood vessels to contract or expand freely) in humans. Green coffee is most often consumed by humans in capsules because of the nauseating odor of the volatile compounds of the green coffee beans.

Recently, two new species of coffee plants have been discovered in Cameroon: Coffea charrieriana and Coffea anthonyi. These species could introduce two new features to cultivated coffee plants: 1) beans without caffeine and 2) self-pollination. By crossing the new species with other known coffees (e.g., C. arabica and C. robusta), new coffee hybrids might allow these new improvements at regular coffee plantations (e.g. in Kenya, since C. arabica and C. robusta are accustomed to these growing conditions).

Coffee of Note

Kona Coffee

Kona Coffee is gourmet coffee grown only one place in the world... on the Island of Hawaii, on the golden Kona Coast, on a very small number of Kona coffee farms... most of them owned by the same kama'aina families for generations. But, there is a difference between one Kona coffee and another. This coffee has developed a reputation that has made it one of the most expensive and sought-after coffees in the world. Only coffee from the Kona Districts can be legally described as "Kona". The Kona weather pattern of bright sunny mornings, humid rainy afternoons and mild nights creates favorable coffee growing conditions.

Coffee trees thrive on the cool slopes of the Hualalai and Mauna Loa Mountains in rich volcanic soil and afternoon cloud cover. Growing in this unique environment, Kona coffee has a distinct advantage over coffees grown in other parts of the world. Coffee trees typically bloom after Kona's dry winters and are harvested in autumn. Coffee cultivated in the North and South districts of Kona on the Big Island of Hawaii is the only coffee that can truly be called Kona Coffee. Kona coffee blooms in February and March. Small white flowers cover the tree and are known as Kona Snow. In April, green berries begin to appear on the trees. By late August, red fruit, called "cherry" because of the resemblance of the ripe berry to a cherry fruit, start to ripen for picking. Each tree will be hand-picked several times between August and January, and provides around 20-30 pounds of cherry.

It is then hand picked, pulped, dried and hulled. Machinery at the coffee mill sorts the beans into different grades by size and shape. Peaberry is top of the line. A peaberry bean is formed when one side of the flower fuses with the other leaving only one bean in the coffee cherry. This gives the peaberry a more concentrated flavor and makes up only about 5% to 10% of the total Kona Coffee harvest. Top grades (in descending order) include extra fancy, fancy, No.1 and prime.

To purchase 100% pure Kona Coffee, check the label. Kona Blend means it only contains 10% Kona beans. These are usually mixed with those from Brazil, Central America, Africa and Indonesia. If you go to the Big Island of Hawaii and the Kona Coast, be sure to check out the numerous farms and coffee mills in the Kona Coffee Belt.

Jamaican Blue Mountain

In 1728, Sir Nicholas Lawes, the then Governor of Jamaica, imported coffee into Jamaica from Martinique. The country was ideal for this cultivation and nine years after its introduction 83,000 lbs. of coffee was exported.Between 1728 and 1768, the coffee industry developed largely in the foothills of St. Andrew, but gradually the cultivation extended into the Blue Mountains.

Jamaican Blue Mountain Coffee or Jamaica Blue Mountain Coffee is a classification of coffee grown in the Blue Mountains of Jamaica. The best lots of Blue Mountain coffee are noted for their mild flavor and lack of bitterness. Over the last several decades, this coffee has developed a reputation that has made it one of the most expensive and sought-after coffees in the world. In addition to its use for brewed coffee, the beans are the flavor base of Tia Maria coffee liqueur.

Jamaican Blue Mountain Coffee is a globally protected certification mark meaning that only coffee certified by the Coffee Industry Board of Jamaica can be labeled as such. It comes from a recognized growing region in the Blue Mountain region of Jamaica and its cultivation is monitored by the Coffee Industry Board of Jamaica.

The Blue Mountains are generally located between Kingston to the south and Port Maria to the north. Rising to 2,300 meters (7,500 ft), they are some of the highest mountains in the Caribbean. The climate of the region is cool and misty with high rainfall. The soil is rich with excellent drainage. This combination of climate and soil is considered ideal for coffee.

Sumatran Coffee

Beans from Sumatra have always been highly prized not only because of their full flavor, but also because of their distinct appearance. Sumatran coffee beans, when green, are often asymmetrical in shape and have a deep aquamarine tint. Beginning in the 18th Century when the popularity of Sumatran coffee rose significantly, the unique shape and hue helped European merchants recognize authentic Sumatran coffee beans.

However, Sumatran coffee’s distinct appearance isn’t the only factor contributing to the coffee’s uniqueness. The unusual drying techniques employed by Sumatran coffee farmers also contribute to the coffee’s distinctiveness. These techniques involve an extended period of the coffee bean’s exposure to the pulp of the berry after the berry has been harvested—a process which is believed to produce deeper tones in the brewed coffee.

Besides the exquisite flavor, the cooperative that grows this coffee has many reasons to be proud of their beans. Known as the Gayo Organic Farmers Association, this coop grows 100 percent organic beans. With the funds from their coffee sales, this community of growers has started a project to bring safe drinking water to more than 1,500 people. The cooperative has also saved funds to help farmers with the reconstruction of their homes, many of which were destroyed in the war, and to aid in the construction of two new schools. This coffee has truly delightful qualities in its origin as well as in the cup.

The most expensive bean in the world is produced in Indonesia. Called Kopi Luwak, it costs $700 US for a kilogram (2.2 lb) and has a flavor that is impossible to imitate. The reason for this is that the Civet cat chews on the ripe cherries and the stone, or coffee bean, is retrieved by farmers once it has taken its natural course through the cat. The bean is then washed and roasted, and the intense odor of the drink comes from the musk secreted by the anal glands of the cat.

Ethiopian Coffee

Ethiopia produces some of the most unique and fascinating coffees in the world. The three main regions where Ethiopia coffee beans originate are Harrar, Ghimbi, and Sidamo (Yirgacheffe). Ethiopian Harrar coffee beans are grown on small farms in the eastern part of the country. They are dry-processed and are labeled as longberry (large), shortberry (smaller), or Mocha (peaberry). Ethiopian Harrar coffee can have a strong dry edge, winy to fruit like acidity, rich aroma, and a heavy body. In the best Harrar coffees, one can observe an intense aroma of blueberries or blackberries. Ethiopian Harrar coffee is often used in espresso blends to capture the fine aromatics in the crema.Washed coffees of Ethiopia include Ghimbi and Yirgacheffe. Ghimbi coffee beans are grown in the western parts of the country and are more balanced, heavier, and has a longer lasting body than the Harrars.

The Ethiopian Yirgacheffee coffee bean, is the most favored coffee grown in southern Ethiopia. It is more mild, fruit-like, and aromatic. Ethiopian Yirgacheffee coffee may also be labeled as Sidamo, which is the district where it is produced. It is grown at the highest altitude in the world, 7,000 ft (2.13 km), and is an unusually good accompaniment to curries. Indonesia has Aged Sukawesi, which is stored in palm-thatched barns under humid conditions for several years. The result is a heavy flavor and a total absence of acidity.

Brewing and Drinking Coffee beans must be ground and brewed in order to create a beverage. Grinding the roasted coffee beans is done at a roastery, in a grocery store, or in the home. They are most commonly ground at a roastery and then packaged and sold to the consumer, though "whole bean" coffee can be ground at home. Coffee beans may be ground in several ways. A burr mill uses revolving elements to shear the bean; an electric grinder smashes the beans with blunt blades moving at high speed; and a mortar and pestle crushes the beans.

The type of grind is often named after the brewing method for which it is generally used. Turkish grind is the finest grind, while coffee percolator or French press are the coarsest grinds. The most common grinds are between the extremes; a medium grind is used in most common home coffee brewing machines.

Coffee may be brewed by several methods: boiled, steeped, or pressured. Brewing coffee by boiling was the earliest method, and Turkish coffee is an example of this method. It is prepared by powdering the beans with a mortar and pestle, then adding the powder to water and bringing it to a boil in a pot called a cezve or, in Greek, a briki. This produces a strong coffee with a layer of foam on the surface.

Coffee may also be brewed by steeping in a device such as a French press (also known as a cafetière or coffee press). Ground coffee and hot water are combined in a coffee press and left to brew for a few minutes. A plunger is then depressed to separate the coffee grounds, which remain at the bottom of the container. Because the coffee grounds are in direct contact with the water, all the coffee oils remain in the beverage, making it stronger and leaving more sediment than in coffee made by an automatic coffee machine.

The espresso method forces hot (but not boiling) pressurized water through ground coffee. As a result of brewing under high pressure ideally between 9–10 , the espresso beverage is more concentrated (as much as 10 to 15 times the amount of coffee to water as gravity-brewing methods can produce) and has a more complex physical and chemical constitution. A well-prepared espresso has a reddish-brown foam called crema that floats on the surface. The drink "Americano" is popularly thought to have been named after

American soldiers in WW II who found the European way of drinking espresso too strong; baristas would cut the espresso with hot water for them. Coffee may also be produced via a cold brew process, in which the water used is not heated before hand. This preparation typically involves steeping coarsely ground beans in cold water for several hours, then removing the grounds with a filter.

American soldiers in WW II who found the European way of drinking espresso too strong; baristas would cut the espresso with hot water for them. Coffee may also be produced via a cold brew process, in which the water used is not heated before hand. This preparation typically involves steeping coarsely ground beans in cold water for several hours, then removing the grounds with a filter.Once brewed, coffee may be presented in a variety of ways. Drip-brewed, percolated, or French-pressed/cafetière coffee may be served with no additives or sugar (colloquially known as black) or with milk, cream, or both. When served cold, it is called iced coffee.

Espresso-based coffee has a wide variety of possible presentations. In its most basic form, it is served alone as a shot or in the more watered-down style café américano—a shot or two of espresso with hot water added, reversing the process by adding espresso to hot water preserves the crema, and is known as a long black). Milk can be added in various forms to espresso: steamed milk makes a cafè latte, equal parts steamed milk and milk froth make a cappuccino, and a dollop of hot foamed milk on top creates a caffè macchiato. The use of steamed milk to form patterns such as hearts or maple leaves is referred to as latte art.

No matter how you like your coffee one thing can be said; as the world becomes more fast paced, coffee drinkers are consuming more and more to keep up. For me, it's a love affair. I enjoy the taste, be it in a cup, coffee flavored ice cream, espresso flavored chocolate truffles, or the fabulous creations coming out of the

kitchens of some of the top chefs in the world. Well, my cup is about empty so it's time for me to get a refill and.......sorry...I've got to run....seems there is a burro trampling my plants! "Hey!....HEY! Mr. Valdez!..... Please get that donkey out of my garden!"

kitchens of some of the top chefs in the world. Well, my cup is about empty so it's time for me to get a refill and.......sorry...I've got to run....seems there is a burro trampling my plants! "Hey!....HEY! Mr. Valdez!..... Please get that donkey out of my garden!"

Bon Appetit!

LouImage Sources: Simon Howden travel.nationalgeographic.com konacoffeeco.com eco-index.org coffeeshop.us chagres.com foto76 coffeetea.info crossingitaly.net en.wikipedia.org telegraph.co.uk Darren Robertson